In the years following Confederation, Ontario does not fail to openly proclaim both its English and Protestant nature, and its attachment to the British Empire. And its elites become increasingly less tolerant of the Francophones who continue to flock to the province from Quebec. The Francophone minority, however – scattered, with limited resources, its only means of affirmation being a few institutions – is far from representing a real danger.

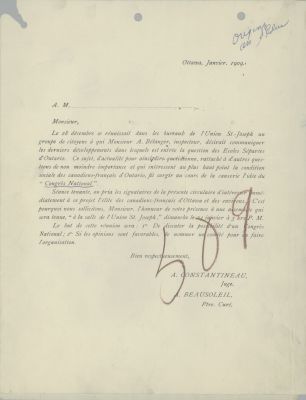

It is the school issue that really stirs up trouble. The Ministry of Education, established in 1876, seeks to create a unique model in Ontario, one which excludes separate schools and French schools. While the former are protected by the Canadian Constitution, it is more difficult to advocate for the latter. The idea of a large provincial association that brings together the driving forces of Ontario’s French community is set in motion.

The Association canadienne-française d’éducation d’Ontario (ACFÉO) is created at the Grand Congrès des Canadiens français held from January 18 to 20, 1910, at the Monument national in Ottawa. This is a landmark event in the history of the Franco-Ontarian community, the first time it exercises its political voice.

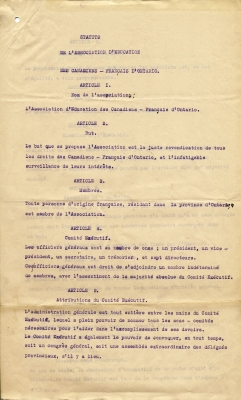

The new organization adopts a structure in keeping with its ambitions: an impressive 25-member board of directors chosen among the religious and political elites of the day, most of them from Ottawa. The Executive consists of a president and two vice-presidents. The Liberal senator Napoléon-Antoine Belcourt, a prominent figure in the capital, is the first to accede to the presidency. The Conservative senator, Philippe Landry, takes the reins of the organization in 1915. In a dramatic gesture that makes him a true national hero, he leaves his position as Speaker of the Senate the following year, thereby breaking his ties with the Conservative Party to maintain full independence in defending the educational rights of French Canadians in Ontario.

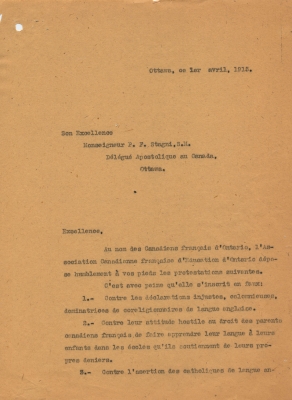

From Ottawa, where it establishes its headquarters, ACFÉO quickly becomes the centre of “resistance” to Regulation 17, which bans “bilingual” schools in Ontario. It is ACFÉO that works hard to lobby the government; that supports, sometimes directly, sometimes indirectly, endless court appeals (Ontarian, Canadian, British); that mobilizes nationalist opinion in Quebec and elsewhere in French Canada; that supports the establishment of “free” schools at the local level; that even attempts to rally Rome around the Franco-Ontarian cause! The struggle is long and difficult.

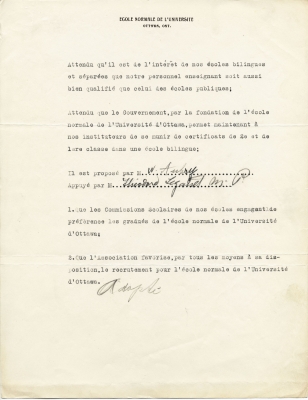

On November 1, 1927, ACFÉO’s efforts are finally rewarded. Following the recommendations of the Merchant-Scott-Côté report and pressures exerted by ACFÉO and Quebec, Regulation 17 is finally abandoned by the Government of Ontario. “Bilingual” schools are restored. But the issue of French-language education in Ontario is far from settled. ACFÉO continues its battle for French-language education in Ontario on several fronts, until 1968 when bilingual schools become completely French, and the private Catholic secondary school system is integrated into the public sphere. But even then, the fight was far from over.

The Monument national, Ottawa, located at 113 George Street, at the corner of Dalhousie, Ottawa, 1910. One of the rallying hotspots for French Canadians in the capital. Copy of a print: Congrès d’éducation des Canadiens-français d’Ontario, ACFÉO, 1910, p. 340.

University of Ottawa, CRCCF, Collection générale du Centre de recherche en civilisation canadienne-française (C38), Ph123ph1-XOFDH-33.