In April 2016, the National Capital Commission (NCC) gives the green light to IllumiNATION LeBreton, a project proposed by the RendezVous LeBreton Group, led by Ottawa Senators owner Eugene Melnyk. The project proposes to create five new neighbourhoods around an events centre and various other public places. The development surrounds a currently buried aqueduct that dates back to a time when the area was part of one of the largest industrial complexes in Canada.

In 1850, the LeBreton Flats are still covered in bushes. It takes only twenty years for the area to become a major centre for the forestry industry, and home to a large working-class population. Francophones account for nearly one-third of this population, and they maintain that concentration until 1901.

The history of the LeBreton Flats is turbulent. Impacted by the depression of the early 1890s, the neighbourhood is completely burned down shortly thereafter, when a fire breaks out in the chimney of a house in Hull in April 1900. “With the wind blowing at over 50 km/h, tons of cordwood, a match factory and large rolls of paper, the fire spreads rapidly”1 as far as Dow’s Lake. The “Flats”, as the neighborhood is called then, are totally destroyed by the flames. But it rises rapidly from its own ashes. In the aftermath of the disaster, the undisputed king of the lumber trade, industrialist J.R. Booth, sends his employees the following telegram: “Pick up the debris [and] prepare to rebuild.”2 The factories are rebuilt, the workers return, and the shops reopen their doors.

Much later, the neighbourhood is once again wiped off the map – this time not by accident, but by choice. The lumber industry is in decline, infrastructure has not been renewed, and housing stock in the mainly working-class area is in poor condition. The Flats do not look very good. On April 17, 1962, Diefenbaker’s federal government announces an urban renewal project for the LeBreton Flats. Following the recommendations of architect Jacques Gréber, the NCC expropriates 65 hectares of land, the equivalent of approximately 2,800 houses. According to historian and archivist Michel Prévost, 3,000 to 5,000 people are displaced. Citizen opposition is powerless.

This time, the LeBreton Flats are not resurrected. Several redevelopment plans are considered over the years, and certain aspects are implemented. The Canadian War Museum is inaugurated in 2005, and some luxury homes are built. But most of the land where several generations of Francophones grew up, started families, worked, laughed and cried, remains vacant. During the winter, snow is dumped on the Flats. Over the summer season, the area hosts one-off events, including the Ottawa Bluesfest, the Ottawa Children’s Festival, classical music concerts and Cirque du Soleil performances. Will IllumiNATION LeBreton finally breathe life back into what was once a hub of French life in Ottawa?

1 Radio-Canada.ca, Ici Ottawa-Gatineau, “L’histoire méconnue des plaines LeBreton,” January 24, 2016 (translated from the original).

2 National Capital Commission, LeBreton Flats – Past, Present and Future | Les plaines LeBreton – le passé, le présent et l’avenir, n.d.

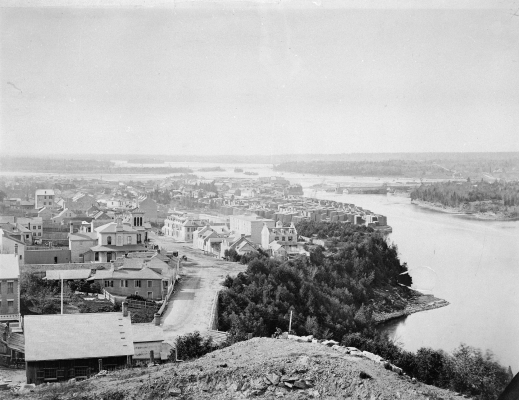

View of Queen Street, westbound, during the Ottawa-Hull fire in 1900 [ca. April 26, 1900]. The great fire of 1900 burns a part of the neighbourhood to the ground and leaves its mark on the urban landscape, six decades before the Gréber plan is implemented.

Source : Library and Archives Canada, Booth family album [graphic material], PA-120334.