Relations between French and Irish Canadians have been marked by rivalry since the early days of Bytown. Arriving initially to work on the construction of the Rideau Canal, the Irish settle on the west bank, at the edge of Upper Town. When they are forced to leave that area at the end of the canal project, a number of them move to Lowertown, which by that time is largely Francophone. The Irish, for the most part unemployed day labourers, try to carve out a place in the timber industry, a sector already dominated by French Canadians who have been cutting trees for over twenty years.

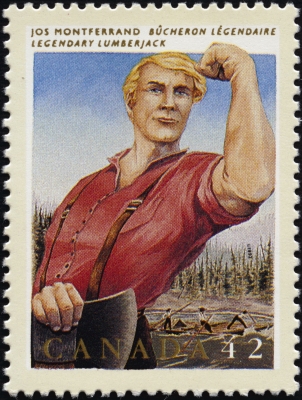

The Irish wage a merciless war, spreading a reign of terror in Bytown. They burn shops and residences, not hesitating to lash out physically at those who resist. A French-Canadian counteroffensive is organized, supported by the Scots, the Protestants and the more conservative classes of Bytown who wish to restore order. Jos Montferrand, a larger-than-life lumberjack character, distinguishes himself by thrashing the “Shiners,” as the French Canadians call the Irish.

Peace returns in the early 1840s, thanks to economic prosperity. But the confrontations of the early days weigh heavily on relations between French and Irish Canadians. In Lowertown, where the Irish represent 31.1% of the population in 1871, tensions run particularly high in Catholic institutions. Language certainly has a lot to do with it, but the ongoing rivalry is also rooted in different visions of Catholicism – to such an extent that, in 1889, Bishop Duhamel establishes a separate parish in Lowertown. St. Brigid’s parish opens its doors to descendants of the first wave of Irish immigrants to the region, as well as those who flee the great famine impacting Ireland in the 1840s. The parish brings together more than 450 families, with its own associations, choirs and sports teams. It also offers schools managed by the Grey Nuns, who also operate Francophone schools. The two populations try to avoid each other, as encouraged by their respective elites.

But a good proportion of the Irish population, propelled by social mobility, gradually leaves Lowertown for the more affluent areas of Ottawa. In 1901, Irish Canadians constitute only 15.3% of the population of Lowertown, which has become predominantly Francophone. Urban renewal takes care of the rest. In 2007, St. Brigid’s Church is transformed into a cultural centre that celebrates Irish culture in Canada.

Irish and French Canadians co-exist for a longer period in Sandy Hill, a select neighbourhood popular with the English and Scottish populations since the late19th century. Sandy Hill’s two Catholic churches – St. Joseph’s for the Irish and Sacré-Coeur for the French – are near neighbors on both sides of Laurier Street, witnesses to an enduring duality.

St. Joseph’s Church on Laurier Ave. At the back, Sacré-Cœur Church is visible, Ottawa, March 1904. Photo: William James Topley.

Source: Library and Archives Canada, Topley Series SE [graphic material], (R639-148-4-E), PA-008992.