In 1967, in the wake of the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism, Ontario Premier John Robarts commits to offering services in French. In 1971, his successor, Bill Davis, makes the same commitment to offering French reception and administrative and judicial services, where numbers warrant. But the reforms are slow, and Ottawa youth grow impatient. They orchestrate a civil disobedience campaign that changes the course of history in French Ontario.

The protest begins with isolated actions. On May 15, 1975, an individual citizen, Raymond DesRochers, appears in provincial court after being arrested for driving with expired license plates and refusing to renew his vehicle registration using an English form. On June 13, Jacqueline Pelletier is incarcerated for refusing to pay a traffic infraction issued in English only. These individual gestures of resistance soon turn into collective action. About 20 other resisters are imprisoned during the following year, in Ottawa and Sudbury.

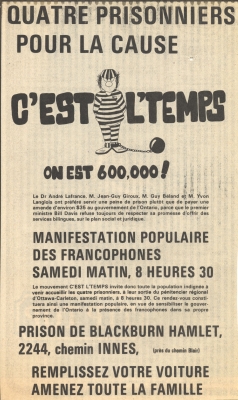

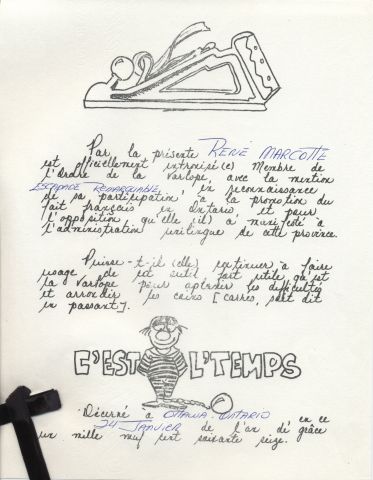

The impact of the first incarcerations convinces protesters to organize into a more structured movement, with action reaching across the entire province. The result: the C’est l’temps (It’s time) movement, born in the fall of 1975. It demands nothing less than the official recognition of Francophones as full citizens. For the time being, it claims the fundamental right of Franco-Ontarians to express themselves freely (i.e., without an interposed translator) in the courts of their province. It further requests that the civil and criminal codes of Ontario be available in French, as they are in Quebec and New Brunswick. The leaders of the movement invite Francophones in the province to refuse to testify in English before the courts and to demand a copy of any legal document in French. Francophones are further urged to insist on bilingual driver’s licenses, bilingual traffic tickets, bilingual change of address forms and publication of municipal by-laws in French and English.

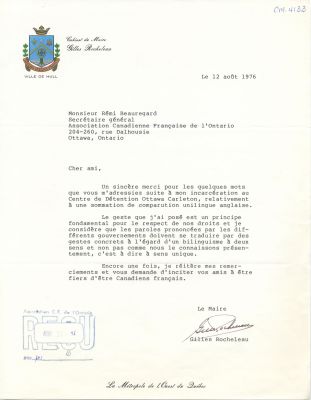

The C’est l’temps movement experiences one of its highlights when four of its members – Yvon Langlois, Guy Béland, Jean-Guy Giroux and André Lafrance – are released from the detention centre in Blackburn Hamlet, east of Ottawa, on November 22, 1975. They were incarcerated for refusing to pay traffic tickets issued in English only. A demonstration takes place outside the prison gates to mark their release, and the scene is broadcast on television. Support for the movement starts pouring in from everywhere.

The battle continues until the summer of 1976 with incarcerations, media coverage, and meetings with provincial leaders. Then the movement runs out of steam, just as the Ontario government demonstrates a definite willingness to put an end to the culture of unilingualism, on the eve of the sovereignty-association referendum in the neighbouring province.

Demonstration at the release of four members of the C’est l’temps! movement from the Blackburn Hamlet Detention Centre, November 22, 1975. Yvon Langlois, Guy Béland, Jean-Guy Giroux, Jacqueline Pelletier and André Lafrance. Photo: François Roy, Le Droit.

University of Ottawa, CRCCF, Fonds Le Droit (C71), Ph92-1532-30529-8.