In 1912, the Government of Ontario adopts a measure that triggers an unprecedented crisis at the provincial scale. Regulation 17 limits French – as the language of instruction and communication – to the first two years of primary education in Ontario schools. As soon as the Regulation is promulgated, Francophones organize themselves and wage a relentless battle to maintain their educational rights. Ottawa is the nerve centre of the struggle.

The crisis has loomed for some time. Already in 1890, the Government of Ontario tries to impose a regulation requiring that all subjects in the educational program be taught in English. Easy to get around by the inspectors applying the regulation locally, it has the effect of pushing several French schools toward the separate school system, which stirs up resentment among Anglo-Protestants, who call for more muscular intervention.

Following the promulgation of Regulation 17, resistance coalesces throughout French Ontario. Ottawa, however, is the site of particularly memorable confrontations. Barely informed of the Regulation that had been adopted, the largely French-Canadian Ottawa Roman Catholic Separate School Board (ORCSSB) decides to openly disobey it, thereby setting the tone for Franco-Ontarian resistance. Its president, Samuel Genest, does not stray from the decision, even when the Ontario government withdraws support for the school board. An injunction obtained by the Irish-Catholic ORCSSB commissioners forbidding the Commission to borrow money on the financial markets to offset its income losses, is not enough to defeat the resistance.

In September 1914, the Commission prefers to suspend teaching rather than submit to Regulation 17. Samuel Genest, however, asks teachers to resume their classes, despite the risk that they will not be paid for their work. The Government of Ontario reacts by deciding to dissolve the dissident school board, replacing it with a committee of three unelected members, a group nicknamed the “Petite commission” by French Canadians. The Association canadienne-française d’éducation d’Ontario (ACFÉO) immediately challenges its legitimacy in the courts.

Meanwhile, in September 1915, the Petite commission decides to dismiss two teachers, Beatrice and Diane Desloges, from the Guigues School for defying the French teaching ban in their classes. The school is deserted, and the Desloges sisters teach clandestinely in various spaces, from vacant shops owned by Alfred Charbonneau at the corner of Dalhousie and Guigues streets, to the Notre-Dame du Sacré-Cœur Chapel on Murray Street. They return to their school in January, under the protection of a group of mothers who, according to an enduring legend, arm themselves with scissors and hat pins.

Not only do they take over management of the school, they also obtain the resignation of Arthur Charbonneau, chair of the Petite commission. A few weeks later, 3,000 children march on Parliament Hill to demonstrate support for their schools. Then, in early February, the 17 ORCSSB schools close their doors. The 4,300 francophone students in the school board subsequently go on strike and march regularly through the city, waving placards. Until it is revoked in 1927, ORCSSB continues to oppose Regulation 17.

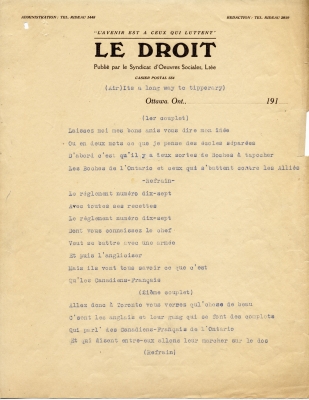

Student picket line in front of the École Brébeuf, protesting the imposition of Regulation 17, which prohibits French as a language of education in Ontario and limits the teaching of French as a subject, Ottawa, February 1916. Photo: Le Droit.

University of Ottawa, CRCCF, Fonds Association canadienne-française de l’Ontario (C2), Ph2-142a.