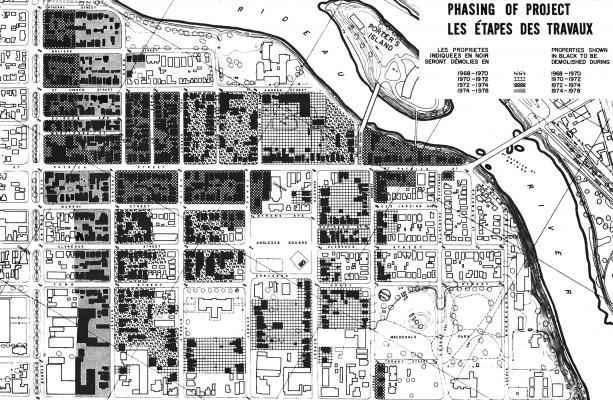

During the second half of the 1960s, hundreds of Francophone families are driven from their Lowertown East homes. The City is embarking on a major urban renewal project in the neighbourhood. On March 22, 1966, Le Droit reports that the project has been designed to “displace virtually none of the 9,363 residents living in the area.”1 The project is supposed to respect “the wishes of the majority of residents, who expressed the explicit desire not to move their homes during a survey conducted by municipal specialists in 1965.” On June 20, 1966, Le Droit also reveals that the expropriation will not affect much of the territory, only 33 out of 180 acres. But the detailed plan produced some 18 months later by the Murray & Murray urban planning firm leaves no doubt as to the extent of the impending changes: the targeted area has more than doubled, and 1,400 families will be displaced.

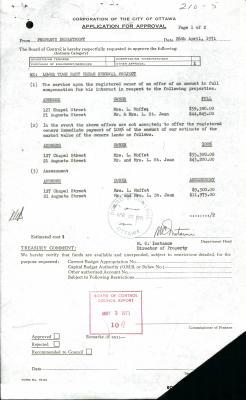

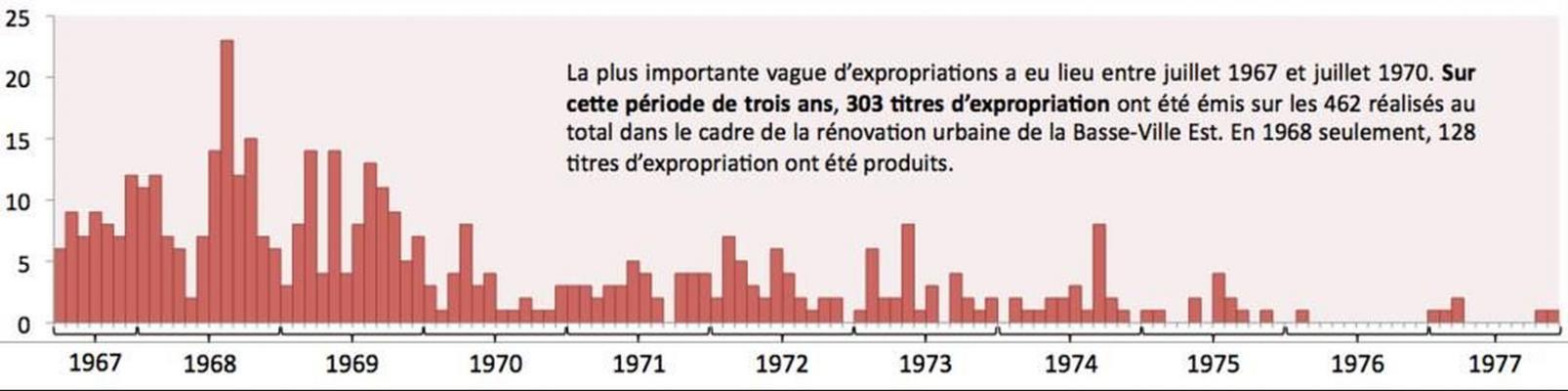

The City begins acquiring properties for demolition in July 1966. Some owners put their properties up for sale voluntarily. Many others are expropriated. Prices are set by the City. The largest wave of expropriations takes place between July 1967 and July 1970, with 303 expropriation deeds issued.

In the winter of 1969, the façades of houses surrendered to the City are marked “O-C” (for Ottawa City) in large red letters. These marks expand the landscape of desolation left by the departure of the neighbourhood’s first residents. Supposedly intended to facilitate the delivery of heating oil, this measure has a collateral effect: neighbouring property owners are impelled to suddenly sell their houses and leave the neighbourhood. Le Comité du réveil de la Basse-Ville (CRBV), formed in November 1968 to defend the interests of neighbourhood residents, describes the act as “demoralizing,” “disrespectful,” “a veritable attack on human dignity,” even an “insult to French Canadians.”

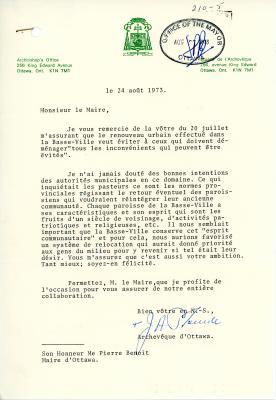

Expropriations and demolitions ultimately impact a large part of the neighbourhood. By the time Archbishop J.A. Plourde lobbies Mayor Benoît, it is too late. Calls from the CRBV for “construction before demolition” go unheeded, and people have no choice but to relocate to Vanier, Alta Vista and other Ottawa suburbs, or to Gatineau. Very few families return to Lowertown East. Those who go back hardly recognize where they are: entire blocks of two- and three-storey houses have given way to high-rise building and concrete replaces brick and wood. Most of the old-time Franco-Ontarian architectural heritage has been lost.

1 Louis Rocque, “Le quartier By demeure français: Ottawa approuve en principe le projet de la Basse-Ville,” Le Droit, March 22, 1966, p. 1 (translated from the original).

Boarded-up houses in Ottawa’s Lowertown prior to demolition. Several hundred houses in the neighbourhood suffer the same fate during the 1960s and 1970s. Photo: François Roy.

Source : University of Ottawa, CRCCF, Fonds Le Droit (C71), Ph92-664-13 902.